Reading assignment rubrics is the first step in any successful writing project. Rubrics are like road maps, and they clarify what your professor expects you to write in your assignment. The assignment rubric has many points which need to be considered before starting your writing. This handout will help you understand your assignment competently and begin to draft an effective response. It will address typical assignment terms and guide you to practice how to apply them effectively to your writing.

What is an assignment Rubric?

Many assignment guidelines follow a basic format. A typical one starts with providing a context for the students, following by setting the writing goals or clarifying the writing expectations and ending with evaluative criteria. These three main components of an assignment guideline will be explained as follows:

The Overview of the Assignment

Assignment guidelines often begin with an overview of the topic. The overview gives some general discussion and background knowledge of the subject of the assignment. In this part of the assignment rubric, professors will be able to introduce the topic briefly or remind you of something relevant that you discussed in class.

The Task of the Assignment

The overview section is followed by providing some prompts using a verb or verbs such as evaluate, summarize, argue, etc., to describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions or questions to get you started. The order of questions sometimes suggests the thinking process you will need to follow to begin the topic. Identifying these prompts and understanding their definitions will direct you to think about the topic in a certain way that your professor expects you to do so. (The prompts with their definitions are listed below.)

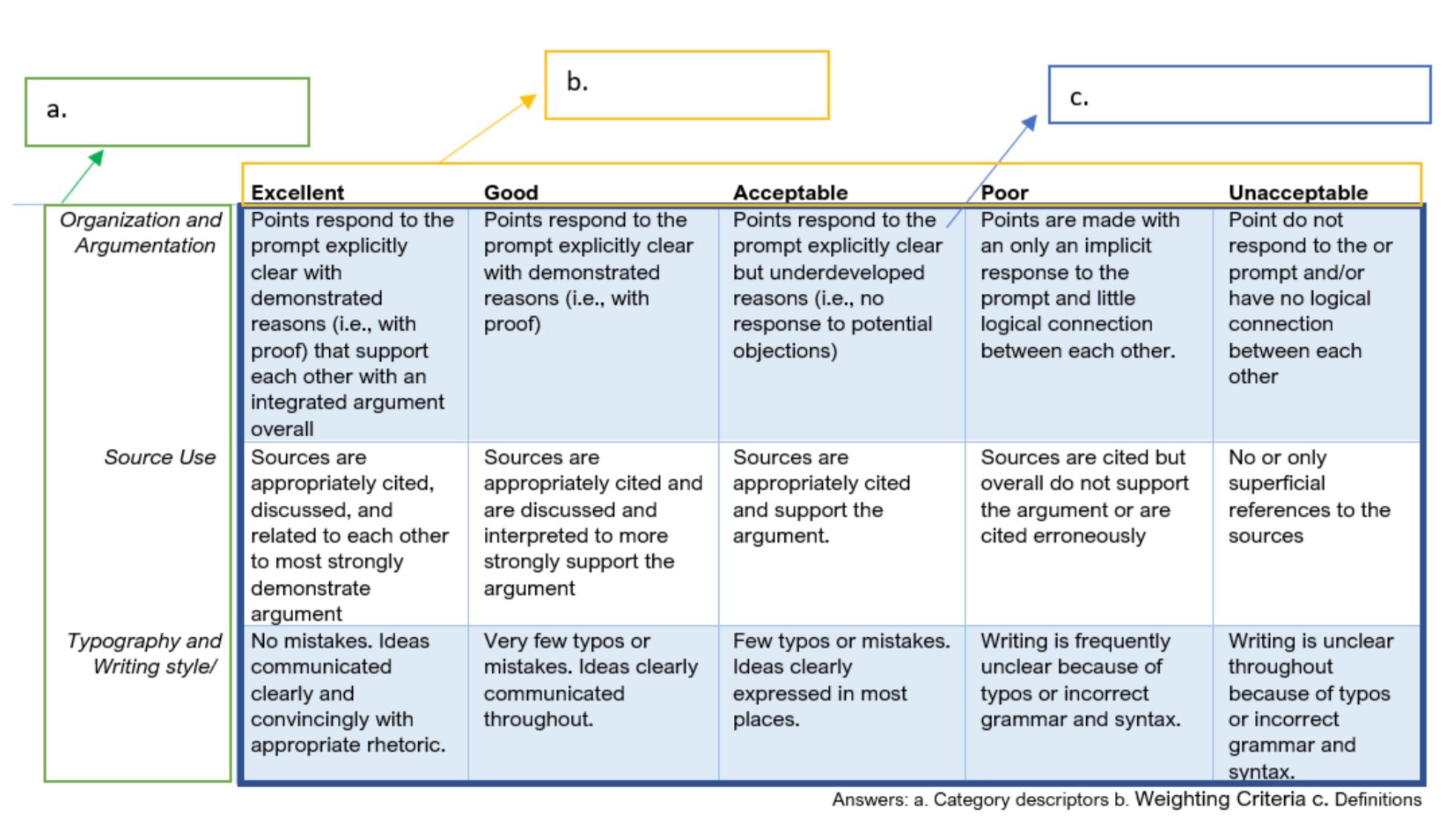

Grading Rubric

The last section of an assignment rubric might include its grading rubrics which provide explicit information about how the writing assignment will be evaluated. For help with this, see our handout on What Is a Grading Rubric.

The prompts

Here are some common keywords or prompts with their definitions to help you think about assignment key terms:

Information Prompts

Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

Identify – pick out what you regard as the key features of something, perhaps making clear the criteria you use

Define—give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

Describe—provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

Explain—give reasons why or examples of how something happened

Illustrate—give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

Summarize—briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

Trace—outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

Research—gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation Prompts

Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

Compare—show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

Contrast; Distinguish—show how two or more things are dissimilar

Apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

Cause—show how one event or series of events made something else happen

Relate—show or describe the connections between things

Comment— Identify and write about the main issues; give your reactions based on what you’ve read/heard in lectures. Avoid opinions.

Interpretation Prompts

Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

Assess—summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

Prove; Justify—give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

Evaluate; Respond—state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

Support—give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

Synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

Analyze—determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

Argue—take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

Interpreting the assignment rubric

Before starting to write and while reading the assignment rubrics, you can ask yourself few basic questions to help you understand why you are expected to write this project and how to achieve it. The questions might be as below:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this task?

Who is your audience?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What should you avoid?

Why did your instructor ask you to do this task?

There might be some reasons that your instructor gives you this assignment. One reason is to assess your understanding of the course material at a particular point in the semester and to give you a grade on what you have learned. However, your instructor wants you to reflect on the topic in a particular way to make sure you have your own specific takeaways and are prepared for experiencing the next steps of learning journey.

Who is your audience?

It is good to think of your audience as someone smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not necessarily someone with background knowledge about the topic.

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

Accordingly, keeping in mind your audience, you will make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey in your writing. Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be colloquial, formal, or objective? And similarly, the level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. Also, it is important to think about the kind of writing style, which is acceptable for your assignment, and is what your instructor expects. 1 For specific help with style, see department specific Style Guides.

What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will be good enough for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Evidence is the facts, examples, or sources used to support a claim. For example, in the sciences, this might be data retrieved from an experiment or a scientific journal article. In the humanities, it may be a quotation from the text, published information from academic critics, or a theory that supports your claims. So, evidence supports your claim, making it more concrete than it would be alone. It is important to use evidence effectively which means integrating it well and analyzing it in a way that relates to your argument clearly and logically. For help with finding credible and effective evidence, visit the Research Help desk at the Patrick Power Library. 2

What should you avoid?

When it comes to writing an academic assignment, there are a few things that you should avoid doing if you want to get the best possible grade.

1. Reading the question incorrectly

One of the most common mistakes students make is not reading the task correctly and thoroughly. This often leads to answering a different question than the one asked. So, make sure you understand what it asks before beginning to write your answer. If the question asks you to talk about a specific topic, make sure you answer that question and do not deviate from it, as it is essential to stay on the topic as much as possible, otherwise, your work may be marked down accordingly.

2. Writing too much or too little

Another common mistake students make is writing either too much or too little. Writing an academic assignment, you need to make sure you stick to the word limit that professors expect and provide only the relevant information.

3. Citing sources incorrectly

When you use information from other sources in your assignment, you must cite them properly. If you do not cite your sources correctly, you could be accused of plagiarism. Resources on using sources can be found at the Writing Centre and Patrick Power Library.

4. Failing to proofread your work

Another common mistake among students is failing to proofread their work. This often leads to incorrect grammar, spelling errors, incoherent and incohesive paragraphs, and incorrect citation. Make sure you read your assignment several times and check for all these mistakes before submitting it. You can also go through your writing drafts with a writing tutor at the Writing Centre to make sure you have not missed any points.

5. Following instructions incorrectly

In most academic writings, several instructions direct you to the specific expectations and show you how the writing goals for the assignment should be achieved and what needs to be done. So, make sure to follow the instructions carefully not to miss out on any important points for your assignment.

6. Generalizing and asking assumptions

Making irrelevant or unnecessary assumptions and generalizations is another common mistake among students. Keep in mind to stick to the facts only and avoid any speculations to succeed (unless you are asked to do so). 3

Conclusion

Critical reading of assignment rubrics helps you with other types of reading and writing projects. If you get good at figuring out what the goals of assignments are, you will be better at understanding the goals of your classes and your fields of study.

Once you have broken down and understood your assignment question, you can start to organize your research and ideas, note them down and specify what claims you want to argue in your essay. For help with the ways to get started, see our handouts on Essay Outline & How to Write a Paper

Bibliography

Too, Gen. “10 Mistakes That Can Spoil Your Academic Assignment.” (2021, December 15). https://kifarunix.com/10-mistakes-that-can-spoil-your-academic-assignment/ (accessed 2 July 2022)

The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Understanding Assignments.”

https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/understanding-assignments/ (accessed 2 July 2022)

University of Guelph.” Write Clearly: Using Evidence Effectively.”

https://guides.lib.uoguelph.ca/UseEvidenceEffectively (accessed 2 July 2022)